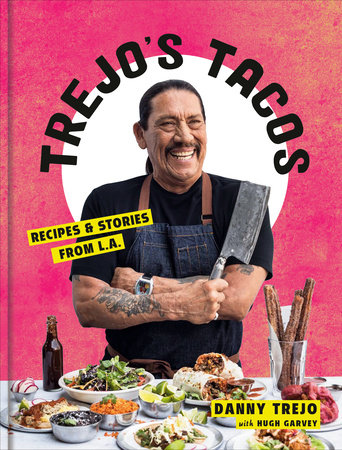

How does a man known for playing merciless, shirtless, tattooed, gun-toting, vengeance-thirsty, knife-throwing tough guys become the face of a restaurant group selling award-winning tacos, authentic

barbacoa, and kale salad? I say this a lot and Trejo’s Tacos is proof of it: It’s not how you start. It’s how you finish.

While I play “the bad guy” in movies, I’ve been a lot of things over the years, including a boxer, a bodybuilder, a drug counselor, and, for a while, a real bad guy—which is how I ended up in San Quentin and Soledad state prisons in the 1960s. It was in prison that I got clean and sober. That was just one chapter in my story—since then, I have been in over three hundred movies, became a father to three kids, and acquired a collection of lowriders, vintage cars, and motorcycles. I still go to the penitentiaries, but now I’m on the other side of the bars as a drug counselor. I’ve traveled around the world at least ten times for my job, but I always come back home to Los Angeles. My life today is very different from what it was in the 1960s. I used to rob restaurants. Today I own eight of them. And we keep growing, with restaurants from Pasadena to Hollywood and LAX to Woodland Hills.

But back to where I started. Home for me in the 1950s and ’60s was a mixed bag to say the least. I grew up in Echo Park long before it became a hipster neighborhood. My family moved to Pacoima in the northeastern corner of the San Fernando Valley, where the sprawl of the L.A. grid glitters until it goes dark against the Angeles National Forest When I wasn’t in prison or getting into trouble, there was always home, and I was always welcome. Even more important than home was Mom, who, no matter whether I was being good or bad, would cook the best food. I loved it. Trejo’s Tacos exists because of that love.

My mom was a killer cook. Back in the 1950s in working-class Latino families—heck, in most working families—it went like this: At the first of the month we would have these elaborate, unbelievable meals: chicken mole, carne asada, and enchiladas stacked high like they do in Texas, where my mom was from. But then by the end of the month, when the money was running out and the rent was due, the dishes wouldn’t have proper names. Mom started making food with whatever we had left in the cupboard. We’d ask, “Ma, what is this?” She’d say, “It doesn’t matter. I just mixed it, you know.” The next night we’d ask and she’d say, “It’s out of the cupboard.” The next night she’d say, “Just eat it. It’s good for you.” And it always was.

These meals are some of my best memories of growing up. We would also have chorizo and eggs for breakfast. Nopales. Chicharrón she’d cook in a green chile sauce and then mix with eggs. Migas stewed until the tortillas were soft.

My dad didn’t share our enthusiasm for food. He’d come home from work and he would just eat. My dad was the Mexican Archie Bunker. He had five brothers. If they made baseball cards for these guys, they would all read “Position: Macho.” Back then the thinking was that your wife should stay home and cook. Only in families where the guys couldn’t make it on their own did the wives have to work. So when I would say, “Mom, let’s open a restaurant!” and we’d talk about what our restaurant would serve and how it would look, my dad would bark: “Why do you need a restaurant? You’ve got a fully functioning kitchen with a freaking O’Keefe and Merritt stove right there!” (O’Keefe and Merritt stoves were big in the 1950s and now they’re collector’s items—if you don’t believe me, just check eBay.) “Both of you can go in there and cook whatever you want.” And so there went that dream.

When I was twelve, my life took a detour when I started hanging out with Uncle Gilbert, my dad’s youngest brother. He was my hero—he taught me how to box, and it turned out I was a natural. He was also the guy who got me into drugs and robbing people. We were literal partners in crime. It got to the point where you weren’t quite sure if you robbed people to support your drug habit or did drugs to support your robbery habit. Through it all, my mom was always there for me, in the kitchen cooking up carne asada or chilaquiles, no matter what. When I was out partying with my friends, we’d all show up in my mom’s kitchen, sometimes at one, two o’clock in the morning. First, my mom would bawl me out for being out so late. Then she’d make us something to eat with a big smile on her face, thanking God I was home. That kitchen was always a safe haven, a place where I could stay out of trouble.

But I never stayed out of trouble for very long. I ended up doing time for armed robbery and drug dealing. In Soledad and San Quentin I put my boxing skills to good use and became a lightweight and welterweight boxing champion, so I would always eat well. Sometimes I wouldn’t even need to go to chow—people would just bring me food. On Saturdays we’d have what we called “spreads,” which are kind of like prison picnics, as much as they could be in a place like the pen—a sort of celebration of life, mostly for the guys that didn’t get visits because they had a falling out with their family, or their wife or girlfriend left them. We took care of each other—we’d all get together and everybody would bring something. Sort of like a potluck. You know that scene in

Goodfellas with all the guys sitting around cooking and eating this big Italian feast? It wasn’t quite like that. Some guys would bring noodles, some guys would bring loose bread, or chocolate, another guy would bring some smuggled-in hooch or homemade pruno, the booze you make by fermenting sugar and cafeteria scraps. We’d all sit out in the yard and have a picnic.

I was in and out of prison for eleven years, and toward the end of that time, I got sober. I remember it clearly. It was Cinco de Mayo, 1968. I made a vow to get clean and to dedicate myself to helping others. When I got out a year later, I started working with ex-cons and other guys who were trying to get and stay clean, too. I worked construction and became a drug counselor. One day one of the guys I was helping stay clean asked me to go visit him on the set of a movie he was working on. This was the mid-’80s and there were a lot of drugs on set and the guy wanted me to be there and help keep him from using. So I go down to the set and I’m watching them film the movie—it was called

Runaway Train and Eric Roberts was the star. The movie took place in a prison, so I felt right at home. In a weird twist of fate, the screenwriter happened to be my old pal Eddie Bunker, who did time with me in San Quentin. He recognized me (I kind of stand out) and remembered that I was a boxer. Eddie hired me to train the movie’s star, Eric Roberts, how to box. The director of the movie, Andrei Konchalovsky, liked the way I looked and cast me as a fighter. That launched my career. From there I started getting roles—you know, for the characters you see listed in the credits as “bad guy #1,” or “scary guy #2,” “tough guy #3,” you get the gist. I eventually worked my way up to Razor Charlie in Robert Rodriguez and Quentin Tarantino’s

From Dusk till Dawn, Trejo in Michael Mann’s

Heat, and Machete in everything from

Spy Kids to

Machete Kills.

So some thirty years and three hundred movies later I’m working on a movie called

Bad Ass with a producer named Ash Shah. He provided much better craft services—or “crafty,” as the movie industry calls on-set catering—than most producers. There were always fresh salads, vegetables, and grilled fish. I like to eat clean and Ash saw that I appreciated the healthy spread. One day we’re eating dinner and he asks me outright, “Danny, why don’t you open a restaurant?” At that moment I almost heard my mom speaking. I felt chills course through my body. But I didn’t really take it seriously, so I just joked, “Sure, and I’d call it Trejo’s Tacos!” I was kidding, but Ash wasn’t. Six months later Ash came to me with a business plan. And it was a great plan. Over the years we’ve learned a lot of things about cooking a new kind of L.A.–Mexican food and we want to share it with you.

Copyright © 2020 by Danny Trejo with Hugh Garvey. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.