INTRODUCTION

The supernatural in literature can be said to have its roots in the earliest specimens of Western literature, if we take cognizance of such monsters as the Cyclops, the Hydra, Circe, Cerberus, and others in Greek myth. There is, however, a question as to whether, prior to a few centuries ago, such entities would have been regarded as properly supernatural; for a given creature or event to be regarded as supernatural, one must have a clearly defined conception of the natural, from which the supernatural can be regarded as an aberration or departure. In Western culture, the parameters of the natural have been increasingly delimited by science, and it is therefore not surprising that the supernatural, as a distinct literary genre, first emerged in the eighteenth century, when scientific advance had reached a stage where certain phenomena could be recognized as manifestly beyond the bounds of the natural. H. P. Lovecraft, one of the leading theoreticians of the genre as well as one of its pioneering practitioners, emphasized this point somewhat flamboyantly in his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature” (1927):

The true weird tale has something more than secret murder, bloody bones, or a sheeted form clanking chains according to rule. A certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; and there must be a hint, expressed with a seriousness and portentousness becoming its subject, of that most terrible conception of the human brain—a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of un-plumbed space.

What this means is that the supernatural tale, while adhering to the strictest canons of mimetic realism, must have its emotional and aesthetic focus upon the chosen avenue of departure from the natural—whether it be a creature such as the vampire, the ghost, or the werewolf, or a series of events such as might occur in a haunted house. If all the events of a tale are set in an imaginary realm, then we have crossed over into fantasy, because the contrast between the natural and the supernatural does not come into play. Conversely, the supernatural tale must be clearly distinguished from the tale of psychological horror, where the horror is generated by witnessing the aberrations of a diseased mind. Lovecraft, in discussing William Faulkner’s tale of necrophilia, “A Rose for Emily” (1930), made clear this distinction, also pointing out the degree to which the supernatural tale is tied to developments in the sciences:

Manifestly, this is a dark and horrible thing which could happen, whereas the crux of a weird tale is something which could not possibly happen. If any unexpected advance of physics, chemistry, or biology were to indicate the possibility of any phenomena related by the weird tale, that particular set of phenomena would cease to be weird in the ultimate sense because it would become surrounded by a different set of emotions. It would no longer represent imaginative liberation, because it would no longer indicate a suspension or violation of the natural laws against whose universal dominance our fancies rebel. (Letter to August Derleth, November 20, 1931)

Given the fact that the commencement of supernatural literature in the West is canonically dated to the publication of Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764), there is no intrinsic reason why Americans need feel any inferiority to Europe in regard to their contributions to the form; for it was just at this time that American literature was itself beginning to declare its own aesthetic independence from that of Great Britain. And yet, less than half a century after the United States became a distinct geopolitical entity, British critic William Hazlitt threw down the following gauntlet: “No ghost, we will venture to say, was ever seen in North America. They do not walk in broad day; and the night of ignorance and superstition which favours their appearance, was long past before the United States lifted up their head beyond the Atlantic wave” (Edinburgh Review, October 1829). Hazlitt may have been seeking merely to emphasize the new nation’s continued cultural inferiority to the land that gave it birth, and he may also have been guilty of exaggerating the rationality that governed the founding of the American colonies, but in spite of all caveats he does appear to raise a valid point. Since so much of supernatural fiction appears to find the source of its terrors in the depths of the remote past, how can a nation that does not have much of a past express the supernatural in literature? The Gothic novels of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were predicated on horrors emerging from the “ignorance and superstition” of the British or European Dark Ages, but if a country did not experience the Dark Ages, how could those horrors be depicted plausibly? The authors represented in this volume, covering nearly the entirety of American history, sought to answer these questions in a multiplicity of ways, and their varying solutions shed considerable light on the development of the supernatural tale as an art form.

Although there is considerable evidence that the British Gothic novel was voraciously read in the United States, few Americans attempted their hand at it: the sole exponent of the form was Charles Brockden Brown (1771–1810), who chose to follow the model of Ann Radcliffe in making use of what has been termed the “explained supernatural,” where the supernatural is suggested at the outset but ultimately explained away as the product of misconstrual or trickery. As a result, Brockden Brown does not qualify as America’s first supernaturalist, and that distinction remains with the unlikely figure of Washington Irving: unlikely because his writing as a whole—lighthearted, urbane, comic, even at times self-parodic—would seem as far removed from the flamboyant luridness of Matthew Gregory Lewis or the guilt-ridden intensity of Charles Robert Maturin as anything could possibly be. And yet, the supernatural comprised a persistent thread in Irving’s work, notably in his two story collections, The Sketch Book (1820) and Tales of a Traveller (1824). That Irving was able to find inspiration in the Dutch legendry of New York and New England—a legendry already two centuries old by the time he began writing—suggests that even a “new” land (new, of course, only in terms of European settlement) could quickly gain a fund of superstition that had the potential of generating supernatural literature.

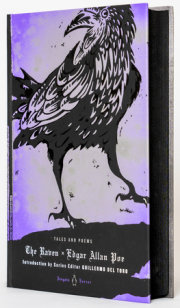

In the next generation, two towering figures—Edgar Allan Poe and Nathaniel Hawthorne—chose starkly different means to convey the supernatural. Hawthorne, plagued by an overriding sense of sin inspired by the religious fanaticism of the Puritan settlers of Massachusetts, found in the American seventeenth century—culminating in the real-life horror of the Salem witchcraft trials—a fitting analogue of the European Dark Ages, and his novels and tales, supernatural and otherwise, constantly draw upon the Puritan past as a source of evil that continues to cast its shadow over the present.

Poe, younger and more forward-looking, felt the need to found his horrors on the potentially hideous aberrations of the human mind, with the result that much of his best fiction falls into the category of psychological horror (“The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Man of the Crowd”). As he noted somewhat aggressively in the preface to Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (1840), in defending himself from accusations that many of his horrors were borrowed from European examples, “I maintain that terror is not of Germany, but of the soul.” And yet, Poe rarely strayed from the supernatural; indeed, many of his most distinctive tales chart the progressive breakdown of the ratiocinative intellect when faced with the “suspension of natural laws.” Poe also recognized that compression was a key element in producing the frisson of supernatural terror: in accordance with his strictures on the “unity of effect,” he understood that an emotion so fleeting as that of fear could best be generated in short compass, and for a century or more his example compelled the great majority of literary supernaturalists to adhere to the short story as the preferred vehicle for the supernatural. Indeed, it could be said that “The Fall of the House of Usher” is a kind of rebuke to those countless British Gothicists who had dissipated the vital core of their supernatural conceptions by extending it over novel length: here, instead, was a “Gothic castle” every bit as terrifying as that of Otranto or Udolpho, but concentrated in a fraction of the space. Poe achieved this condensation by a particularly dense, frenetic prose style that could easily be mocked (and would in fact be mocked by such a fastidious writer as Henry James), but whose emotive power is difficult to gainsay.

Poe, then, is the central figure in the entire history of American—and, indeed, British and European—supernatural fiction; for his example, once established, raised the bar for all subsequent work. No longer could such entities as the vampire or the ghost—already becoming stale through overuse and, more signifiantly, through the advance of a science that was rendering them so implausible as to become aesthetically unusable—be manifested without proper emotional preparation or the provision of at least a quasilogical rationale; no longer could fear be displayed without an awareness of its psychological effect upon those who encounter it. And yet, over the next half-century or more after Poe’s death, we can find no writer who focused singlemindedly upon either supernatural or psychological horror as Poe had done; indeed, excursions into the supernatural emerged almost at random from writers recognized for their work in the literary mainstream. This may indeed suggest that the supernatural was not, properly speaking, a genre clearly dissociated from general literature, but a mode into which writers of all stripes could descend when the logic of their conceptions required it.

And so we have the examples of F. Marion Crawford, popular historical novelist, writing the occasional short story, and even one or two novels, of the supernatural; it may or may not be significant that these short stories were collected only posthumously in the volume Wandering Ghosts (1911). Another popular writer, Robert W. Chambers, began his career writing a scintillating collection of the supernatural, The King in Yellow (1895), but lamentably failed to follow up this promising start, instead descending to the writing of shopgirl romances that filled his coffers but spelled his aesthetic ruination. Edward Lucas White, also better known for his historical novels, persistently recurred to the supernatural in his short stories, notably in two substantial collections, The Song of the Sirens (1919) and Lukundoo (1927).

If any figure can be said to have followed in Poe’s footsteps, it is the sardonic journalist Ambrose Bierce. From the 1870s until his mysterious disappearance in 1914, his occasional “tales of soldiers and civilians” danced continually on either side of the borderline between supernatural and psychological horror. Bierce became the hub of a West Coast literary renaissance that featured other writers such as W. C. Morrow, Emma Frances Dawson, and even the young Jack London, all of whom dabbled in the supernatural. Short fiction comprised only a relatively minor proportion of Bierce’s total literary output—he was best known in his time as a fearless, and feared, columnist, chiefly for the Hearst papers—and, while he may have derived inspiration both from Poe’s example and from his theories on short fiction construction, the literary mode he evolved could not have been more different from Poe’s: a prose style of stark simplicity and spare elegance, a detached, cynical, occasionally misanthropic portrayal of hapless protagonists in the grip of irrational fear, and a probing utilization of the topography of the West in contrast to the never-never lands of Poe’s imagination. Indeed, Bierce successfully answered Hazlitt’s old query by showing that even a land as raw and new (again, in terms of Anglo-Saxon settlement) as the West could be the source of terror: the abandoned shacks and deserted mining towns of rural California become the mauvaises terres of the Biercian imagination, lending a grim distinctiveness to tales whose relatively conventional ghosts and revenants might otherwise relegate them to second-class status. And of course Bierce followed Poe in the meticulous etching of the precise effects of the supernatural upon the sensitive consciousness of his fear-raddled protagonists.

If Bierce was the head of the West Coast school of weird writing in his time, Henry James was, perhaps by default, the leader of the East Coast school. Like so many other mainstream writers, he found the supernatural—manifested almost exclusively in the form of ghosts—a perennially useful mode for the expression of conceptions that could not be encompassed within the bounds of mimetic realism. And yet, James rarely tipped his hand unequivocally in the direction of the supernatural, instead mastering the technique of the ambiguous weird tale, where doubt is maintained to the end whether the supernatural has actually come into play or whether the apparently ghostly phenomena are merely the products of psychological disturbance on the part of the characters. Preeminent among James’s contributions in this regard is The Turn of the Screw (1898), which has inspired an entire library of criticism debating whether the revenants at the focus of the tale are or are not genuinely manifested; clearly James did not wish the question to be answered definitively. In short stories written over an entire career he probed the same questions, and his final, fragmentary novel, The Sense of the Past, might have been his greatest contribution to weird literature had he lived to complete it. James’s compatriot Edith Wharton manifestly followed in his footsteps—perhaps, indeed, at times a bit too closely. Nevertheless, there is enough originality and artistry in her dozen or so ghost stories to earn her a place in the supernatural canon.

H. P. Lovecraft joins Poe and Bierce in the triumvirate of towering American supernaturalists. In a career that spanned little more than two decades, Lovecraft transformed the horror tale in such radical ways that its ramifications are still being felt. Although an early devotee of Poe, Lovecraft was also a diligent student of the sciences and came to the realization that the standard tropes of supernatural fiction—the ghost, the vampire, the witch, the haunted house—had become so played out and so clearly in defiance of what was then known about the universe that alternate means had to be employed to convey supernatural dread. Lovecraft found it in the boundless realms of space and time, where entities of the most bizarre sort could plausibly be hypothesized to exist, well beyond the reach of even the most advanced human knowledge. This fusion of the supernatural tale with the emerging genre of science fiction (canonically dated to the founding of the magazine Amazing Stories in 1926) generated that unique amalgam known as the Lovecraftian tale. In such tales as “The Call of Cthulhu,” “The Colour out of Space,” “The Whisperer in Darkness,” At the Mountains of Madness, and “The Shadow Out of Time” Lovecraft exponentially expanded the scope of supernatural fiction to encompass not just the world, but the cosmos.

Lovecraft fortuitously emerged as a literary figure at the exact time when supernatural horror could finally be said to have become a concretized genre, with the founding of the pulp magazine Weird Tales in 1923. This was in every sense a mixed blessing. It is now difficult to determine whether the establishment of Weird Tales (the first magazine exclusively devoted to horror fiction) and its analogues in the realms of mystery, science fiction, the Western, romance, and other genres actually precipitated the banishment of the supernatural (except by the most eminent mainstream authors or in suitably tame and conventional modes) from leading literary magazines, or whether their prior banishment led to the founding of the pulps; whatever the case, a manifest dichotomy was established, and those writers who chose to focus on the supernatural found themselves obliged to appear in the pulps for lack of other venues. Simultaneously—perhaps as a result of the literary Modernism that dominated the 1920s, with such writers as Theodore Dreiser, Sinclair Lewis, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Ernest Hemingway—a prejudice developed among mainstream critics for any literary product that departed from strict social realism, so that virtually all ventures into fantasy or the supernatural were indiscriminately declared subliterary. This prejudice—based upon the very real fact that the great majority of material in the pulp magazines was indeed trite, hackneyed, and subliterary—took decades to dissipate, and in large part it caused Lovecraft’s work to languish in the pulps, so that his friends had to band together after his death to publish his work in book form.

Nevertheless, during his lifetime Lovecraft attracted a wide cadre of like-minded writers who were determined to raise supernatural horror to the level of an art form, even if some of them perforce wrote to the narrow demands of Weird Tales and other pulps. Clark Ashton Smith, who had already established a reputation as a scintillatingly brilliant poet, produced more than a hundred tales that fused fantasy, science fiction, and horror in an indefinable amalgam, while Robert E. Howard, in his short career, definitively established the subgenre of sword and sorcery as a viable component of the supernatural or adventure tale.

Lovecraft’s most valuable influence was exemplified in his patient and tireless tutoring of younger writers—August Derleth, Donald Wandrei, Frank Belknap Long, Robert Bloch, Fritz Leiber—into the finer points of literary artistry, and his laborious efforts paid dividends in the generation after his death. Other writers who had not had any direct contacts with Lovecraft, such as Ray Bradbury and Richard Matheson, nonetheless benefited from the example of his relatively small but extraordinarily rich output of weird work. Derleth and Wandrei established Arkham House as the leading publisher of supernatural work—another mixed blessing, as their publications tended in part to enhance the relegating of supernatural horror to a literary cul-de-sac. But such dynamic writers as Bloch, Bradbury, and Leiber followed Lovecraft in expanding the range of the supernatural by melding it with elements drawn from the mystery or suspense tale, the fantasy tale, and the science fiction tale.

This melding had, by the 1950s, become a necessity, because the pulp magazines were in their last throes. Weird Tales finally folded in 1954, and no replacement was in sight: the magazine Unknown (later Unknown Worlds) had had a short but influential run in the 1940s, but that was all. The pulps gave way to digest magazines, chiefly in the realms of fantasy and science fiction (whose readership was, and today remains, much larger than that for supernatural horror), while the paperback book generated potential markets for mystery, the Western, science fiction, and fantasy, but not for horror. Accordingly, such writers as Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont were compelled to write supernatural tales under the guise of these other genres—perhaps a natural development in an era when the threat of atomic annihilation caused an entire society to ponder the mixed blessings and dangers of scientific and technological advance.

For writers of the 1950s, the Lovecraft influence manifested itself even in the way in which they consciously strove to battle against it. Writers such as Matheson, Bradbury, and Beaumont, while admiring Lovecraft, came to regard his work as too remote from everyday reality for credence in an age in which television, radio, and film were celebrating the nuclear family and the American way of life. They also protested against the occasional flamboyance of Lovecraft’s prose, so contrary to the skeletonic syntax of a Hemingway or a Sherwood Anderson, and so easily parodied—especially, and unwittingly, by a host of self-styled disciples who sought to mimic Lovecraft’s lush texture and elaborate upon his Cthulhu Mythos. Accordingly, Matheson and his compatriots fashioned tales emphatically, perhaps aggressively, set in a recognizable world of telephones, washing machines, and office jobs. This tendency had been anticipated by Fritz Leiber, who in “Smoke Ghost,” “The Girl with the Hungry Eyes,” and other tales of the 1940s nonetheless managed to fuse Lovecraftian cosmicism with mundane reality. That latter story was pioneering in a different way: in its baleful account of the dangers of sexual obsession, it had introduced a bold new element to a genre that had otherwise seemed almost prudishly chaste.

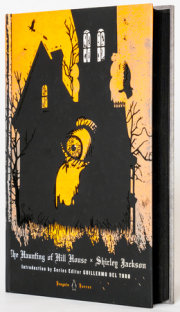

From a very different direction, the mainstream writer Shirley Jackson found in both supernatural and psychological horror a vital means for conveying her pungently cynical skepticism regarding human motives and actions. The fact that many of her tales appeared in The New Yorker and other prestigious venues helped to break down the resistance of magazine editors who had axiomatically banished the supernatural from their pages. Well-paying men’s magazines such as Playboy began specializing in mystery, horror, and science fiction, and the occasional supernatural tale even found its way into such staid organs of literary classicism as the Atlantic Monthly and Harper’s.

Media, especially film and television, now began to cast an increasingly significant influence upon supernatural literature. The dominant figure in the field in the 1960s was a television personality, Rod Serling, whose The Twilight Zone (1959–64) immediately and permanently entered into the American collective psyche. While Serling was in fact a skilled writer, it was his aloof, sardonic commentary on his television show that rendered him an icon in his own time. At the same time, the crude B-movies of the 1950s—rightly condemned as pablum for the uncultured or as self-parodic camp—slowly improved in cinematic quality. Perhaps this fusion of literature and media laid the groundwork for what would become a three-decade “boom” in horror literature.

Such bestselling novels as Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby (1967), William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist (1971), and Thomas Tryon’s The Other (1971) were all adapted into successful films, especially the first two. Horror suddenly became a blockbuster genre, and Stephen King was the first to capitalize on it: such of his early books as Carrie (1974), ’Salem’s Lot (1975), and The Dead Zone (1979) all benefited from striking film adaptations, and King went on to become perhaps the most remarkable phenomenon in publishing history. It is, of course, naïve to think that the number of copies an author happens to sell has any correlation with his or her literary standing, and the majority of King’s writing is indeed marred by clumsy prose; hackneyed conceptions derived from film, comics, and other media; and a rather dreary prolificity that does not bode well for the endurance of his work. King’s success as a horror novelist also spelled, at long last, the downfall—at least as a publishing phenomenon—of the short story as the chosen venue for supernatural horror, even though the number of cases in which a supernatural plot can be said to be sufficiently rich and complex to be sustained over novel length is, in spite of the thousands of novels that have poured off the press in recent decades, disconcertingly small.

To be sure, not all the writers who strove to grab a residue of King’s commercial success were hacks or tyros, although there certainly were, and are, a distressing number of these. Such a writer as Peter Straub (Ghost Story, 1979) may have indulged in a bit of self-congratulatory exaggeration when he declared that King was the Dickens of the horror tale while he himself was its Henry James, but there is no denying that his artistry as a prose stylist is substantially greater than King’s. Although Anne Rice’s first supernatural novel, Interview with the Vampire, dates to 1976, it took some time in becoming a bestseller; her following now may be even greater than King’s, and some of her works (mostly her early novels) are far from contemptible on the purely literary scale. Dean R. Koontz, on the other hand, can take his place with Judith Krantz and Danielle Steel as bestsellers whose work will be deservedly forgotten in the next generation.

The current emphasis on the horror novel, whether supernatural or psychological, is largely a marketing phenomenon: in today’s publishing environment, short stories are not seen as commercially viable. And yet, King himself had begun his career with some highly able short stories, collected in Night Shift (1978), and other writers of the 1970s continued to be devoted to the short form regardless of the slim pecuniary profits to be derived thereby. T. E. D. Klein, although the author of one novel, The Ceremonies (1984), that briefly reached the bestseller lists, has made an imperishable name for himself by excelling in that hybrid form, the novella, which allows for expansiveness in the conveyance of the supernatural manifestation while at the same time adhering to Poe’s “unity of effect.” Dennis Etchison, Karl Edward Wagner, and others may also find their short work surviving as literary contributions while the novels of their contemporaries—and, indeed, their own novels—lapse into oblivion. For these writers, the small press has become the haven for their weird work; pay is slight or perhaps nonexistent, but there is something to be said for writing that is largely divorced from market considerations.

In this regard, the most remarkable phenomenon in contemporary supernatural horror is Thomas Ligotti, whose eccentric output of short stories (he has admitted that he will not and cannot write a horror novel) has somehow managed to secure a following almost entirely through word-of-mouth. Uncompromising in his uniquely twisted vision of a universe of grotesque nightmare, Ligotti is content to offer his meticulously crafted tales to a relatively small audience capable of appreciating it; like Lovecraft, he scorns the notion of writing to a market. If Ligotti ever appears on the bestseller list, it will be an aberration more bizarre than anything depicted in his tales.

The 1990s were a period of ferment in the horror field. The “boom” that had begun in the 1970s seemed to be dying of inanition—and, perhaps, of an overdose of the mediocre, the shoddy, and the calculatingly commercial. Some writers and critics gleefully predicted the downfall of the supernatural and its replacement by either the serial-killer novel or other forms of psychological suspense, while still others, protesting against “dark fantasy”—a mode of writing that sought to convey its horrors by subtle implication rather than blood and gore—found a loud alternative in the subgenre labeled splatterpunk. This name—a variant of the avant-garde science fiction mode called cyberpunk—was coined by David J. Schow, who proved to be nearly the sole writer of this sort whose work has any hope of survival as a genuine contribution to literature. Melding references to slasher films, rock-and-roll music, and true crime, splatterpunk writers proclaimed their greater relevance to a society in which violence had become so prevalent as almost to be banal; but in the end, the sheer absence of talent exhibited by most such writers caused this movement to flare out almost as quickly as it had emerged.

Today, supernatural horror comes in as many forms as the imaginations of its diverse writers can envision. Once again—with the exception of Joyce Carol Oates, who has followed Shirley Jackson in repeatedly evoking the supernatural in the course of her mainstream work—the predominant venue is the small press, and in recent years the Internet has proven to be a welcome haven for much sound work. It is at this juncture difficult to determine which authors will survive the relentless winnowing of posterity: in my judgment, at least Caitlín R. Kiernan and Norman Partridge deserve tentative canonization, although others might wish to make a case for such writers as Brian Hodge, Douglas Clegg, Patrick McGrath (a leading figure in the “New Gothic” movement, which strives to return to the Gothic roots of the genre and bypass the excesses of both the old-time pulps and the recent bestsellers), Jack Cady, and any number of others.

As a literary mode, the supernatural has undergone as many permutations and variations in the past two hundred and fifty years as any other, and has left a rich legacy of literary substance that deserves to be chronicled and interpreted. For writers like Lovecraft, it may have chiefly represented “imaginative liberation”—liberation from the mundane, the everyday, the commonplace—but for others, like Shirley Jackson, it was a vehicle for the conveyance of conceptions about humanity and its relations to the cosmos beyond that offered by mimetic fiction. To the extent that it draws upon the past—in the form of myth, legend, and superstition that persistently suggests a world of shadow behind or beyond that of ordinary reality—it appears to represent a permanent phase of the human imagination, and as such it will remain perennially vital as a literary mode. Its emphasis upon fear, wonder, and terror may perhaps render it a cultivated taste, but the flickering light it casts upon these darker corners of the human psyche will bestow upon it a fascination, and a relevance, to those courageous enough to look upon its revelations with an unflinching gaze.

—S. T. Joshi

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.